What would happen if you woke up seeing angels? What if God told you that you are the chosen one? Would you believe Him?

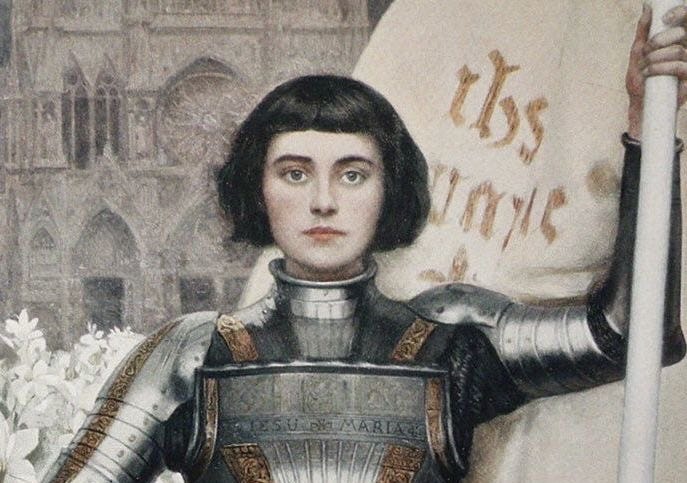

If your answer is yes, let me tell you that you would probably have been declared a saint during the Middle Ages and now you would be featured on a mosaic in some church. However, in the 21st century, many of those biblical stories—like that of Joan of Arc, who claimed to have divine contact—seem like simple tales invented by religion to maintain power. But, what if I told you that, for those people, those experiences were as real as the sky being blue is to you?

These types of experiences are known as religious psychosis or mystical delusions, where the patient claims to have divine contact or a special purpose given by God.

First, it’s important to understand what psychosis is, as it’s not just about someone with a knife screaming nonsensical things. Psychosis is not synonymous with violence. It is a group of mental disorders where the person distances themselves from reality and perceives it in an altered way. The main symptoms are hallucinations and delusions.

Hallucinations are sensory perceptions that have no real basis: they can be visual, auditory, olfactory, etc. On the other hand, delusions are false beliefs, out of touch with reality, that the person considers absolutely true, despite having no evidence. Among the most common are delusions of jealousy, persecution, or grandeur.

Diseases such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or delusional disorder may include these symptoms. Often, delusions try to make sense of a previous hallucination. The problem is that it’s not enough to just tell someone, “that doesn’t exist,” because, for them, it is totally real.

Imagine that I show you a box and you clearly see it as red, but I insist that it is blue. What arguments could you give me to convince me otherwise? Exactly: none. And that’s what happens in psychosis. For the patient, what they live is their truth.

That’s why we talk about religious psychosis when hallucinations or delusions have spiritual content: people who believe they are possessed, that God has given them a message, that they have been chosen, or even—and quite commonly—that God has abandoned them or is punishing them.

It’s important to note that religious psychosis does not appear as an independent diagnosis in the DSM-5, but rather as a type of delusion or hallucination. Nevertheless, studies on the impact of religion on mental disorders are recent and still limited. In the past decade, research has started to delve deeper into its effect, both positive and negative, on mental health.

When the delusion includes the idea of being “the chosen one” or having a direct connection with God, it is often followed by deep depression once the psychotic episode ends: everything they believed fades away, leaving a void that is very hard to manage.

Even when the psychotic disorder is not religious in nature, faith can significantly influence the patient. Three main ways in which religion manifests in psychotic diseases have been identified:

Religious attachment: occurs when the person develops an anxious relationship with God or a spiritual figure. Often, those who have emotional deficiencies seek this bond in the divine. But since it is an intangible figure, this relationship cannot respond to their emotional needs, which can generate more anxiety, guilt, and a sense of abandonment. For example, a 2015 study by Huguelet et al. found that patients with psychosis were more likely to form this kind of attachment, and doing so worsened their delusions and anxiety. It has been observed that, even outside of a psychotic context, this can contribute to disorders like bulimia.

Religious coping: is the use of faith to face a problem. Here we distinguish two types: positive (RPC), which helps the person find comfort and meaning, and negative (RNC), which can be very harmful. The latter appears when one believes that suffering is a divine punishment or that God is not listening. Studies have shown that this type of coping increases self-harm, anxiety, and stress.

A similar concept is what is called spiritual bypassing, where the patient uses religion to cope with a problem, grief, or difficult emotional situation. If this happens occasionally and moderately, it does not necessarily cause negative harm. In fact, it could be considered one of the most natural and functional uses of religion: offering comfort, giving meaning to suffering, and allowing the individual to stay afloat in moments of crisis. However, when this resource becomes a permanent strategy that suppresses emotions or is justified by a negative interpretation of faith, it can have harmful effects, such as increasing psychological distress or deepening the disconnection from the patient’s emotional reality.

Spiritual struggle: it is divided into three types:

• Supernatural: conflict with entities like God, the Devil, Heaven, etc.

• Interpersonal: conflict with other people or religious institutions.

• Intrapersonal: internal conflict related to faith or morality.

Many psychotic patients develop existential concerns like death, the meaning of life, or good and evil, questions that religion often answers. That’s why it’s easy for psychosis to evolve toward religious content.

In summary: religion, by itself, does not cause psychosis. But in contexts of vulnerability, it can trigger or become a component of the disorder. Therefore, it is essential to consider the patient’s beliefs when treating psychosis: they can be a source of support, but also a risk factor.

To close, let’s briefly analyze some cases that, in my opinion, clearly reflect religious psychosis:

Joan of Arc: She has been attributed with disorders such as schizophrenia due to the hallucinations she claimed to experience. She said she heard divine voices and saw saints.

Carrie’s mother (1976 movie): After the loss of her husband, she faces her pain through extreme religiosity, which turns into a delusion. She believes the world is corrupted by the Devil and that her daughter is possessed.

Each and every one of us, as humans, has diverse beliefs and thoughts that affect the way we behave, act, and see our problems. Religion should not be separated from psychology, as both play in the same field. That’s why collaboration is essential to ensure that these studies continue and more and more patients can be helped. This is not about attacking faith, but about studying it to understand what it might entail. Because the crazy one is not the one who deludes, but the one who refuses to help.